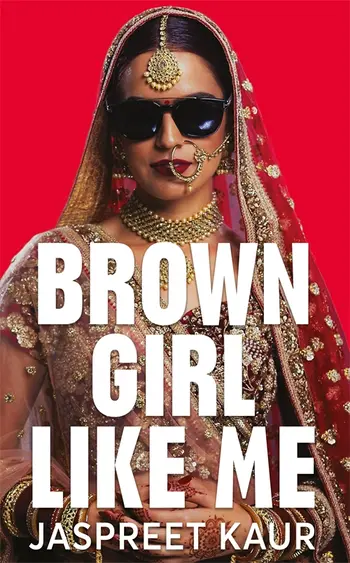

The title of this blog post is from the book, Brown Girl Like Me, By Jaspreet Kaur. Subtitled, The Essential Guidebook and Manifesto for South Asian Girls and Women, it tackles the complicated, multi-layered, and often painful existence of South Asian women with honesty, lived experience, empathy, research, and quotes from a variety of brown women and others. Intended to be a letter to all brown girls, no matter their age or what stage they may have reached in their life-span, brown girls and women will recognise the familiar, the difficult and the taboo.

Jaspreet Kaur is a spoken word artist, history teacher and writer. Brown Girl Like Me is a fantastic read, engaging and absorbing. The book opens with a ritual and rejection I immediately recognised. “Sundays would always mean one thing in my house, when I was a kid. Hair-wash day. This ritual is probably one of my earliest memories, me sitting at my mum’s feet whinging as every knot passed through the comb, followed by a generous amount of coconut oil being rubbed into my head and finished off with a nice, neat plait. This precious time with my mum was a mixture of haircare and storytime.” A few years later, this cherished time and ritual, is rejected by Jaspreet when she overhears a group of English schoolgirls sniggering about curry smells and her “greasy hair”. I also have similarly nostalgic memories of my mother oiling my hair, and of me rejecting the ritual as I became older and aware of derogatory comments. I wonder how many thousands of us in the diaspora, broke these exquisite threads, as we grappled with the complexities impacting us.

Women are mythologised out of their own agency, culturally conditioned out of their self-worth, and philosophically stripped of their right to dignity. Recognition and discussion of these, and other forces such as religion and racism began to be discussed by a scattering of brown women in the 1970s. Awaz, possibly the first brown feminist group, came together in London, and included Gulshun Rehman*, Amrit Wilson, myself, and several other women. Some of us were also members of a group which established the UK’s first refuge for South Asian women and children fleeing domestic violence. Apart from the regular meetings, when we discussed and examined the layers constricting, conditioning and moulding brown women, Awaz participated in anti-racist struggles, defence campaigns, and organised protests against immigration practices such as virginity testing, described in the blog post Virginity Tests and Self-Defence. We were clear that we would define our own feminism, and critiquing our culture didn’t mean a rejection of our background. A few of the women from Awaz went on to set up Southall Black Sisters and others joined forces with black women to create the umbrella organisation OWAAD (Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent). In the 80s a group of women began to publish the magazine Mukti, aimed at South Asian women. During the intervening decades, brown feminism has contributed to the South-Asian community’s development and prosperity, although many deeply rooted practices and beliefs still continue to limit and reduce the lives of many brown women, and by extension the whole community. One phase of feminism paves the way for the next, each one answering the imperatives of the time.

Brown Girl Like Me is an important addition to feminist progress. The book’s nine chapters, each beginning with one of Jaspreet Kaur’s poems, cover political, public, private and taboo issues, ranging from cultural appropriation, education, employment, dating, relationships, being gay, menstruation and mental health.

“Am I dying?” begins the section where twelve-year-old Jaspreet is hit with the first of many panic attacks: “My heart felt like it was about to burst out of my chest, my body was consumed by cold sweats. I could barely breathe. It felt like a plastic bag had been wrapped around my head…” For years she never told anyone what she was going through, silenced by the stigma surrounding mental health issues in the South Asian community; a fearful culture of secrecy, burdened by misconceptions, superstitious beliefs and religious ideas such as karma. Breaking the topic into subsections, Jaspreet brings in the roles of patriarchy, its negative influence on the well-being of brown women and men; the profound, yet barely acknowledged area of inter-generational trauma. Including other mental health concerns, such as the denial of eating disorders and post-natal depression. Recounting the story of Nima, a young mother from California, who suffered post-natal depression and took her own life in 2020, the book describes the reaction of South Asians: “Nima’s death sent shock waves through social media, triggering the hashtag #BreakTheStigma4Nima.” Jaspreet describes how starting to journal, write poetry, and get therapy have helped her over the years. The book flags-up several organisations such as southasiantherapists.org, Taraki,and Gaysians; including SOCH Mental Health, (‘Soch’ means thought) “who are directly tackling the conversation taboo within South Asian communities.” A quote from Poorna Bell, whose husband suffered with depression and addiction, eventually committing suicide, stresses the importance of tackling silence and stigma: “By talking, we can create a space for people going through something similar, to reach out before it’s too late…That is the spirit of community and a key path to prevention.”

Brown Girl Like Me provides many ideas and tools for brown women. Advocating self-care and self-love, the author makes clear that nourishing self-care is distinctly different from selfishness, as many may be tempted to label it. The chapter on raising a brown feminist discusses the importance of providing a bedrock of nurturing love, encouraging empathy, reading, teaching financial literacy, discussion, and includes a quote from Rupinder Kaur, founder of Asian Women MEAN Business (AWMB) and mum of two. “I encourage them (her children) to question everything …if I don’t know the answer, we will seek it out together.”

The chapter on Power In The Digital Age, recognises the new opportunities to speak out and be seen. Jaspreet describes the spat between Azelia Banks and Zayn Malik, when Banks accused Malik of stealing elements of her ‘Chasing Time’ video. Conducted over Twitter, the conflict became quite ugly with Banks using slurs such as ‘sand nigga.’ ‘faggot,’ and even attacking Malik’s mother calling her a ‘dirty refugee … ,’ before turning her attention back to Malik and labelling him a ‘curry scented bitch.’ In the following days, something amazing happened. The hashtag #curryscentedbitch started popping up all over the place, and it wasn’t due to One Direction fans defending their star. “… the young Asian female diaspora across the globe took ownership of the slur. Despite the phrase being directed at a young Asian man …images of young brown women were filling up the feeds of Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.”

Some reviewers have critiqued the book for not being academic enough or for lapses in information. No book can do everything. Each book demands careful judgement and balance, forcing the writer to make difficult choices. Brown Girl Like Me is full of passionate energy and infused with the desire to pass on knowledge and life lessons that could help many a brown girl and woman.

*****

*Gulshun Rehman has worked in the UK charity and international development sector, concentrating on programmes protecting the rights of women and girls in resource poor settings. In the 1980s, she helped to set up East London’s first refuge for Asian women and children of south Asian descent, and is a founding member of the Newham Monitoring Project, created to defend the rights of victims of racial and police harassment. A resident of East London, Gulshun has also worked in Palestine, Bangladesh, India and Uganda. Currently, she is a trustee of the East End Women’s Museum, which seeks to record, research, share and celebrate the stories of East London women, past and present.

Leave a Reply