In 1944, as WW11 raged across continents, the school district in Columbus, Ohio, held an essay competition, challenging students to address the question “What to do with Hitler after the War?” A sixteen-year-old African-American girl, thought long and hard about the question. And won the competition with an essay of one sentence: “Put him in a black skin and let him live the rest of his life in America.”

In the winter of 1959, Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife Coretta, visited India. Garlanded upon their arrival and celebrated on the streets of old Mumbai and Delhi, they stayed a whole month at the invitation of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Whilst travelling through south India, in the city of Trivandrum, they were invited to visit a school for students from the untouchable caste. At the school, the headmaster introduced King thus: “Young people,” he said “I would like to introduce to you a fellow untouchable from the United States of America.”

King was stunned. And not a little annoyed at being referred to as an untouchable. Till he began to consider even more profoundly the reality of black people’s lives in America: consigned to the lowest levels of society for centuries, smothering in a cage of generational poverty, quarantined in isolated ghettoes, unprotected by law and government, forever subject to arbitrary violence and brutality at the hands of the dominant white people. “Yes, I am an untouchable, and every Negro in the United States of America is an untouchable.”

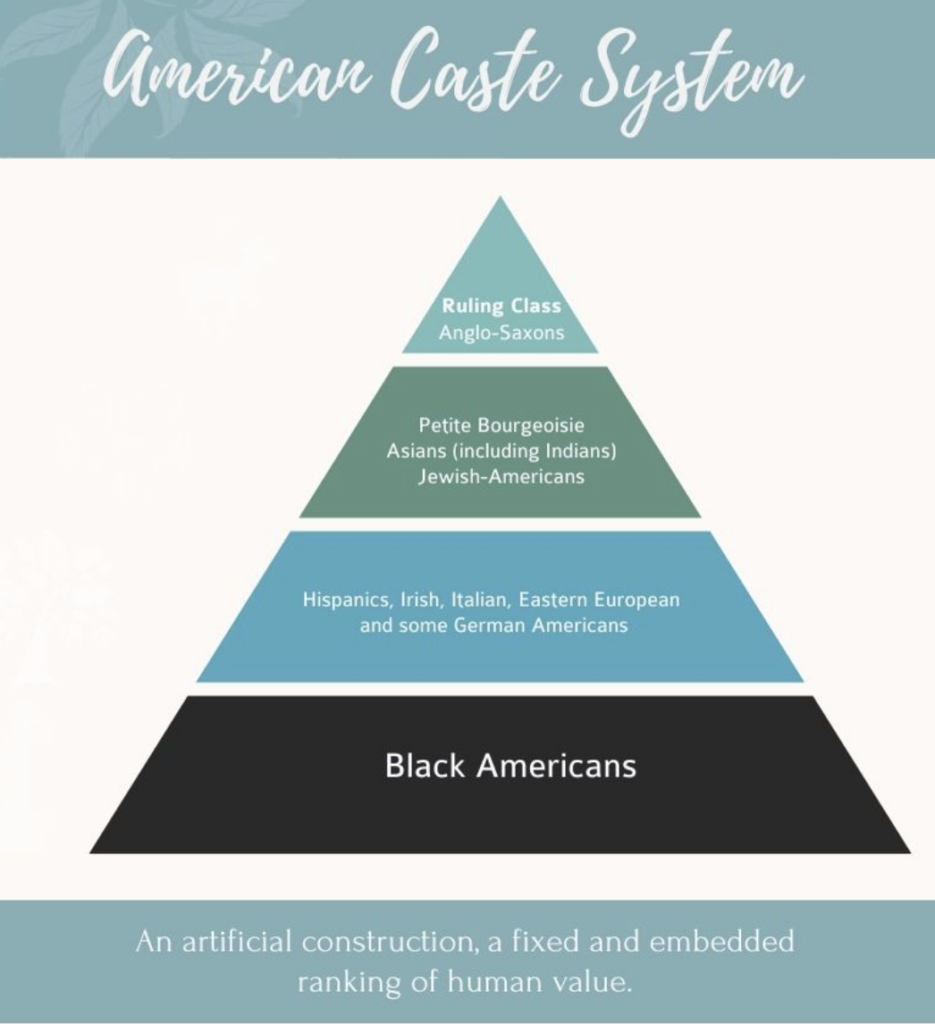

‘In that moment, he realized that the Land of the Free had imposed a caste system not unlike the caste system of India and that he had lived under that system all his life. It was what lay beneath the forces he was fighting in America.’ Writes the African-American journalist Isabel Wilkerson in her revelatory, absorbing and riveting book, Caste, subtitled, The Origin of Our Discontents. In these few words, laying bare the poison running through American society, the foundational fracture endangering its safety and future.

To name something is to know it. To recognise its face and history, function and purpose; to immediately comprehend the value and status, or unworthiness and lowliness to be attached to it. Wilkerson describes the insidious, almost-unseen pattern at work in American society, ‘A caste system has a way of filtering down to every inhabitant, its codes absorbed like mineral springs, setting the expectations of where one fits on the ladder.’

Caste is Wilkerson’s second book and was a New York Time’s bestseller. Wilkerson’s prose carries a poetic beauty and empathy, immediately engaging, fluent and truthful. Impeccably researched, the book’s argument comes over as a human necessity, drawing us into a monumental injustice and tragedy that plays out everyday on the streets of America. Slavery may have been abolished in 1865, but caste lives on. No country can have a caste system and not be infected by its consequences: a corrupted legal system, a divided society, democracy endangered. At one point Wilkerson uses the phrase ‘A karmic debt beyond accounting,’ potently underlining the moral rot a caste system creates. Additionally, Wilkerson answers a question millions of us have asked: why does Donald Trump have such fanatical followers and why did so many vote him into the White House in 2016; Wilkerson puts her finger on the heart of the matter: ‘…they were voting for caste.’

‘The hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality,’ Wilkerson asserts. ‘It is about power — which groups have it and which do not.’

Wilkerson illustrates her analysis with powerful human stories, igniting our hearts and minds. Such as the story of Wylie McNeely. In 1921, in the Texan village of Leesburg, nineteen-year-old Wylie McNeely was tied to a stake, accused of assaulting a white girl, his protestations of innocence falling on deaf ears. Kindling was placed around the stake. Five hundred people had gathered to watch the entertainment. Before the match could be lit, the leaders of the lynching had to settle an important issue. ‘The leaders drew lots to see who would get which piece of McNeely’s body after they had burned him alive, figure out the body parts “which they regarded as the choicest souvenir.” This they did in front of the young man facing his final seconds on this earth,’

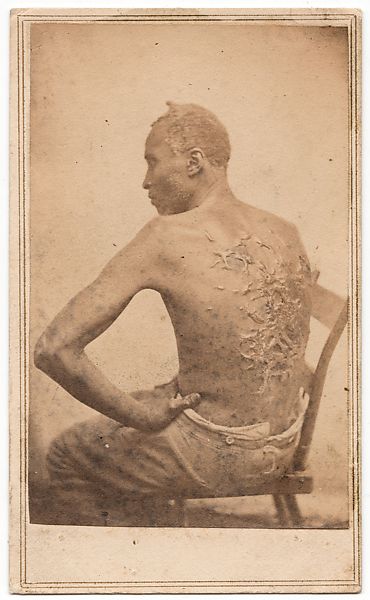

‘Caste is fixed and rigid,’ says Wilkerson, making the distinction between class and caste. Whilst class can provide chinks of opportunity, there’s no escaping caste. Insidious, entrenched, inculcated from childhood, so that it seems natural and ordained, part of the very air. Wilkerson unpicks the threads and names The Eight Pillars of Caste, which create, justify, and keep the unholy system running. The pillars include religion, inherited traits such as skin colour, myths of purity and pollution, and the unrelenting use of cruelty and terror.

Slave owners became amongst the richest people in the world, their fortunes underpinned by a culture of constant whipping and barbarity. Wilkerson quotes the historian Edward Baptist, “Whipping was a gateway form of violence that led to bizarrely creative levels of sadism,” southern enslavers employing waterboarding, mutilation and more, whilst minimising the horrors they practiced, unwilling to admit, as Baptist wrote “…that they lived in an economy whose bottom gear was torture.”

A deliberate denial, perhaps unsurprising in a society where Native Americans were occasionally skinned and made into bridle reins. Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the U.S. a slave owner, himself used bridle reins made out of Native American flesh, when he went out riding on some handsome steed.

In the twentieth century, in Germany, June 1934, when a committee of Nazi bureaucrats met to discuss the mechanics of how to create a rigid new hierarchy, to isolate Jewish people from Aryans, they looked west, to the white race across the Atlantic and ‘… began by asking how the Americans did it.’

Comparisons with the caste system in India, weave in and out of Wilkerson’s book. A brilliant, Ph.D. student from India, a Dalit from the untouchable class, studying at an American university, is triggered at the very idea of talking to ‘upper caste’ Indian students at the same university. The Dalit student verbalises his feelings, perhaps speaking for every human being trapped at the bottom of a caste system: “It is a feeling of danger…They are a danger to me. I feel danger with them.”

As do African-Americans when faced with white people. The murder of George Floyd, the killing of Breonna Taylor in her own home as she slept, the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery by a white father and son, were no aberrations but part and parcel of centuries of unremitting violence and lynchings. Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit,’ the words rasping through her throat, her eyes closed in pain, become witness and lamentation.

During slavery, black people were used not just for unremitting labour, but also for horrific medical experiments, without anesthesia and certainly no consent. After slavery, many decades later, their hard-won gains were regularly destroyed by vigilante violence. “A white mob massacred some sixty black people in Ocoee, Florida, on election Day in 1920, burning black homes and businesses to the ground, lynching and castrating black men, and driving the remaining population out of town, after a black man tried to vote. The historian Paul Ortiz has called the Ocoee riot the “single bloodiest election day in modern American history.”

Caste has been Included in the New York Times 1619 Project, an on-going initiative to reframe America’s history, putting the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the heart of the country’s narrative.

Caste underlines the need for the Black Lives Matter movement, and every other movement seeking to dislodge America from its ancient hatred. ‘Our era calls for a public accounting of what caste has cost us, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, so that every American can know the full history of our country, wrenching though it may be.” Wilkerson declares in the book.

Courageous and beautifully written, Caste not only throws light on America’s divisions, but brings into focus the UK’s class system, and its symmetry with caste. Caste teaches us again that all human division, whether based on race, class or gender, is an exercise in power.

When the book was first published Oprah Winfrey announced that Caste was her Summer 2020 pick for Oprah’s Book Club and proclaimed it “the most essential…the most necessary-for-all-humanity book that I have chosen.” I echo every word.

Excellent piece. Really affected me.

Thanks. Appreciate your comment.