On 31st July 1940, Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville Prison, in London.

On 29th July 2017, I went to see the poignant and heart-breaking documentary about the partition ‘Rabba Hun Ki Kariye – Thus Departed Our Neighbours.’

In one of its early scenes letters are being read, from a prisoner who was in Brixton jail in 1940, England. He is insisting the authorities must officially use the name he’d given them: Mohammed Singh Azad. Clearly not an average name, combining Muslim, Sikh and ending in the Indian word for Freedom. In some places the name is recorded as Ram Mohammed Singh Azad, adding a Hindu name. He was the man we know as Udham Singh.

Intrigued by the fact he’d been held in Brixton prison, a place I’d driven past a thousand times, often glancing at its forbidding gates and walls, on 3oth July 2017 I sat down to research him, and thus discovered he’d been hanged on the 31st, 77 years ago.

The coincidence may be a day apart, but date and place felt like a connection through time. Often, our lives seem to hang on slender threads of chance, seemingly unrelated events, and the heritage of history. If, in 2017, those of us from the Indian sub-continent, are lucky enough to be stewards of our own destiny, it’s due to those who’ve gone before us. 2017 is also the 70th anniversary of India’s independence. And India’s holocaust, the Partition.

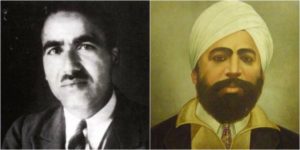

Udham Singh emerges from history, as a man with many names, as the ‘Forgotten Revolutionary,’ but also as the ‘Avenger of Jallianwala Bhag.’ His name changes began early in life. Named Sher Singh by his parents, at the age of 5 he and his brother were orphaned and grew up in Khalsa Orphanage in Amritsar, where, during Sikh initiation rites, he was given the new name of Udham Singh and his brother became Sadhu Singh.

In later years, as he travelled across many countries, and supported India’s independence struggle, he used several aliases: Ude Singh, Sher Singh and Frank Brazil. But perhaps the name which meant the most to him, was tattooed on his arm: Mohammed Singh Azad. During his travels, through East Africa, and America, he kept in contact with other freedom fighters such as Bhagat Singh, whom he admired greatly.

While he was in the States, Bhagat Singh asked him to return to India. He obliged and returned with 25 men and some firearms in 1927.

Later he was imprisoned by the British authorities for five years. In that time Bhagat Singh, and two others, Rajguru and Sukhdev, were hanged for their revolutionary activities. On his release, Udham Singh soldiered on, but continually harassed by the police, escaped abroad.

Eventually coming to Britain. Here he worked as a carpenter, motor mechanic, and rather bizarrely, as an extra in two films by Alexander Korda, Elephant Boy (1937) and The Four Feathers (1939). In this photograph, Udham Singh is the one standing in the middle.

He attended the Shepherds Bush Gurdwara (at that time the only Gurdwara in Britain I believe). The photograph below (taken in 1938) shows him making chapatis for langar, the communal meal. The same Gurdwara my father also attended some 20 years later, and where he must also have helped to prepare langer.

Udham Singh was arrested on 13th March 1940 at Caxton Hall. When arrested he said that he’d only meant to protest, not to kill anyone, asserting his willingness to be imprisoned or to die. ‘I just shot to make protest. I have seen people starving In India under British Imperialism. I done it, the pistol went off three or four times. I am not sorry for protesting.’

Udham Singh Arrested and Being Led Away

Times of India Blogs.

I find this an intriguing change to the normal image of a fire-breathing revolutionary. Perhaps Udham Singh had recognised that ideas last longer than bullets, and had meant to draw attention and publicity to the act which linked him to Sir Michael O’Dwyer, a former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab in British India, rather than a violent revenge. He would have known full well, the punishment visited on him may be out of all proportion to the act.

On that fateful day he attended a meeting at Caxton Hall, and fired several shots. A man from the audience started to struggle with him, and despite Udham Singh’s intentions Sir Michael was killed.

Unknown to either at the time, the connection between Udham Singh and Michael O’Dwyer had begun in Amritsar, on 13th April 1919, at the appalling massacre of a peaceful gathering in Jallianwala Bhag. Udham Singh was present, along with others from the orphanage, serving water to people protesting against the British, and people who had arrived from surrounding villages for the Sikh festival of Baisakhi. At around 5.30 pm, General Reginald Dyer entered the Bagh with his troops, and sealed off the only exit. He ordered his troops to fire, and they went on till all their ammunition was exhausted. In all 1,650 rounds were fired. More than a thousand people were killed, and several thousand lay wounded. There was none to give them medical aid when they were struggling between life and death.

Udham Singh’s young brother and sister were killed in the massacre. Leaving him all alone in the world.

The atrocity sent shock waves through India, but the Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab, the same Sir Michael O’Dwyer (no relation to General Dyer), endorsed General Dyer’s actions and termed it a ‘correct action.’ The young Udham Singh had survived but was forever scarred by the event. The seeds for the protest shooting, Michael O’Dwyer’s death, and his own hanging on 31st July, had been sown.

In the statement after his arrest he said: ‘I am not sorry for protesting. It was my duty to do so. ….

I do not mind my sentence. Ten, twenty, or fifty years or to be hanged. I done my duty.‘

During his imprisonment in Brixton jail, Udham Singh went on hunger strike for 36 days, till the authorities strapped him down and force-fed him through a tube.

At his trail, which many sources say was short and chaotic, Udham Singh made a blistering final speech against British imperialism, which the presiding judge forbade the press to publish. He reiterated his willingness to die for the freedom of India, and repeated ‘I never meant anything; but I will take it.’

Navtej Singh, who has written a book on Udham Singh, says: “Udham Singh was not an assassin, simply propelled by the desire for revenge. He was a political revolutionary — a member of the Ghadar Party — who was aware of his actions and wanted to make a point against British imperialism.”

The orphan child whose journey ended on 31st July 1940 in a hangman’s noose, said of his death: ‘What greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland.’

And 77 years later, I think about the effect of his life and death, on my life and those of my generation.

In 1974, Udham Singh’s remains were exhumed and repatriated to India. His ashes were scattered in the Sutlej river, in which the ashes of other freedom fighters, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev had also been scattered.

On Udham Singh’s 75th death anniversary in 2015, the Indian band Ska Vengers honoured him by releasing an animated music video on his life, ‘Frank Brazil’.

Now, when I drive past Brixton prison, and glance at its security gates and high walls, I’ll think of Udham Singh, alone in his cell. Of his protest and sacrifice for a better world.

Udham Singh

What a man a true patriot he will live on when. The brutal British Empire is finally finished, I can a an irish Republican identify with his noble actions,

It is a great article. I shall appreciate if you can give me reference for Udham Singh coming to India with arms and 25 men on Bhagat Singh’s request and interacting with him in 1927. I shall be highly obliged.

regards

Harish Jain

Have replied.