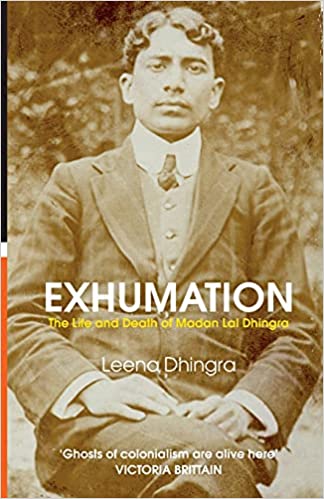

‘Schools don’t teach us about Indian history or Independence,’ complain thousands in the Indian Diaspora. All those keen to learn more about their historical and social inheritance, should immediately get themselves a copy of the recently published book Exhumation, subtitled The Life and Death of Madan Lal Dhingra, and written by the actor Leena Dhingra; whose role in a Partition episode of Doctor Who, re-ignited her own and her family’s experience: ‘That’s my story, my history, my trauma…’, she’d declared.

Dedicated Whovians may recall, the episode was called ‘The Demons of the Punjab,’ by Vinay Patel; the plot revolving around Sunday 17th August 1947, when the notorious Radcliffe Line was announced, splitting the Punjab, families and homes; unleashing catastrophic violence and dislocation.

Exhumation is three stories in one, connected by Leena Dhingra’s research into Madan Lal’s story and her own search for a sense of identity and belonging – a search echoed by many in the Indian Diaspora. The first story is of the revolutionary Madan Lal Dhingra, born in Amritsar, who assassinated Sir Curzon Wyllie in London, and was hanged at Pentonville Prison on 17th August 1909. The second story is of Madan Lal’s wealthy, anglophile family headed by Rai Sahib Doctor Ditta Mal Dhingra, whose sons bought their suits from the family tailor in New Bond Street. The third story is of Leena Dhingra’s branch of the family, who suddenly found themselves refugees when Partition occurred.

The book covers the passionate Indian Independence movement in London, in the early twentieth century, focused around India House (65 Cromwell Road, Highgate, N6 5HH), ostensibly set up as a hostel for Indian students studying in London, but also a meeting place and an engine for fierce discussions and campaigns …. covertly watched by the police. The sections on the Dhingra family provide a fascinating insight into the social layers underpinning British rule, and the knife-edge these families negotiated. Leena’s story, occurring in the second half of the twentieth century moves between Paris, London and India, as she travels between schools, family and countries. Including fascinating social snippets which pop up now and again, such as the advice to young English men, embarking on an Indian career “above all, never, ever let a native see you naked.” Or Indian school children having to learn the ‘Ten Great Blessings of British Rule.’

In the gallery of Indian freedom fighters, Madan Lal Dhingra hasn’t been as well-known as others, such as Udham Singh, who was also executed at Pentonville Prison 31 years later, for assassinating Michael O’Dwyer, in revenge for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. As Leena notes in the epilogue, ‘Only two freedom fighters were executed in London, both Punjabis, both from Amritsar. Both finally exhumed in the 1970s and returned to India.’

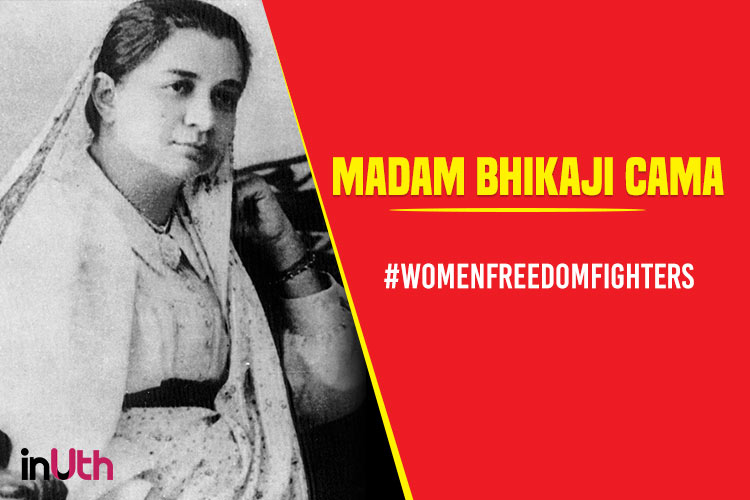

Exhumation gives life, colour, and content to Madan Lal; presenting a complex, socially aware young man; somewhat at odds with his successful, anglicised family. The book also brings to the fore many whose names have fallen out of sight, such as Madam Bhikaji Cama, whom I’d never heard of before, but who certainly deserves her place in the pantheon of revolutionary movers and shakers. Cama supported Varma in founding the influential Indian Home Rule Society; wrote, published and distributed revolutionary literature, and together with Vinayak Savarkar designed the first version of the Indian flag. Which Madan Lal was astonished to see on his first visit to India House, immediately asking about it. ‘This is the flag of Free India,’ replied Savarkar. ‘Madame Cama is mostly responsible for it. The green band is the colour of the Muslims and the eight stars in it represent the eight provinces of India. This middle band of saffron is the colour of the Buddhists and Sikhs and it has the Bande Mataram (‘(We) bow to thee Mother (India)’) in it. And the red band is the colour of the Hindus. It has the orb and crescent of Islam in it.’

India House becomes Madan Lal’s alma mater, as he grapples with the nature of colonial tyranny, the morality of violent or non-violent action, the conflicting demands of family and country. Wrestling with his dilemmas, Madan Lal visits Madam Cama and comes away with her motto: “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.” Ultimately, Madan chooses to join the small group of trusted young men who put themselves forward for ‘the test’, to determine which one of them has the guts to become an assassin.

I first heard of Madan Lal Dhingra and ‘the test’ years ago, in a meeting of the Asian Women Writers’ Collective, when Leena talked about wanting to write his story. We’d been riveted as she’d described how each young man had stepped forward, turn by turn, and held his hand over a naked candle flame. The one who held his hand there the longest would earn the right to kill Sir Curzon Wyllie. (Popplewell quotes The Indian Sociologist as describing Wyllie and Lee Warner … as “old unrepentant foes of India who have fattened on the misery of the Indian peasant every (sic) since they began their career”). Out of the group, Madan Lal proved to be the one, and thus chose his fate.

Over the intervening years, I’d remembered the ‘candle test’ story, particularly when I came across Madan Lal, while researching Udham Singh and the Indian independence movement. I must say, I found myself disappointed at the depiction of this critical event in Exhumation: practically devoid of Madan’s feelings, no reference to any inner battle or struggle to hold on to his resolution, or the searing agony he must have been enduring.

After the assassination, the Dhingra family in India is thrown into desperate panic, trying to save Madan Lal by claiming he was mentally unstable, firing off telegrams, and immediately despatching two of the older brothers to Simla, to see the Viceroy’s Private Secretary and assure him of their loyalty and abhorrence at Madan’s action. In London, while Madan Lal sits in prison, awaiting trial, Indians loyal to the British, hold meetings of condemnation.

Shifting further along the timeline: in 1947, Leena’s father, who teaches at Government College, Lahore, accepts a temporary secondment to UNESCO, and the family leave for Paris, unaware of the tsunami soon to be unleashed on the Punjab. When Partition occurs, with the slowness of communications at that time, the family is initially unaware that Lahore has been allocated to Pakistan, that they’ve lost everything and have become refugees.

At a later stage, Leena’s mother, who ‘loved walking and talking,’ tells her stories of their past, ‘of Lahore… ‘the perfect city,’ … friends and friendships … ‘At Divali, our Muslim friends would send us gifts and sweets wrapped in red and at Eid we would send them sweets and gifts wrapped in green.” Including what the atmosphere was like around the hanging of the young and charismatic Bhagat Singh, in March 1931: ‘…they (the British) kept the date a secret, so we never knew when it was going to happen. We would guess and there would be rumours. There was this big Congress Session in Lahore and before the session we all sang “Bhena tusi gao kodiya, Datta Bhagat Singh chad gaye ghodian,” which means “Sisters sing auspicious songs, Datta and Bhagat Singh have mounted their bridal horses.” I wept and wept and wept. We all did. The whole hall was weeping.’

As the years pass, as Leena matures into adulthood, her mother’s dream of building a new home, is echoed in Leena’s own search for a sense of belonging and her efforts to deal with the past: ‘Just a well of pain, of Partition: full of fears and unformulated questions.’ At one point her sister names the unnamed, the trauma caused by Partition, and says that trauma kills instinct. An insight which many may recognise. If instinct is the unconscious compass by which we steer our lives, its absence would create dissonance and dislocation. ‘I was a girl from India, a girl from Paris, a refugee from Partition, a coloured girl, but beyond those labels, who was I?’ Leena asks at one point.

A well written and absorbing book, I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. However, I would’ve been grateful for a family tree, often having to stop and work out who was who in the sprawling Dhingra family, particularly as the narrative covers four generations. A contents page would also have been useful for locating the differing stories. Additionally, Leena’s personal story could have benefitted from stricter editing, about two-thirds of the way through, as a sense of repetition began to occur.

Exhumation is an engrossing read, evoking the drama of tumultuous times and the consequences borne by those who get caught in history’s gears. It’s a carefully researched book, containing extracts from British intelligence reports, private diaries, family letters, newspapers and more. Exhumation should definitely be on school curricula and university courses. And of course, on people’s bookshelves; get yourselves a copy everyone.

Leave a Reply