Introduction:

This is a far longer post than I normally write. I wanted to mark the anniversary of Udham Singh’s execution at Pentonville Prison, but as I’d already written a post on him last year, Udham Singh, The Lonely Revolutionary, this year I decided to place him within the revolutionary struggle forming the turbulent landscape propelling his destiny.

I’ve been surprised to see that Udham Singh, The Lonely Revolutionary is one of my most regularly viewed posts, indicating a real interest in the independence struggle and the freedom fighters; those incredibly courageous men and women who gave up everything, risked danger and prison, endured torture and pain, but who also put forward a vision for a free, secular India where all were equal.

Raising the haunting question: what would our lives be like today if not for them? And would we have the same courage to defy a brutal and barbaric power? As I started researching, I found myself drawn into this compelling subject, making it absolutely necessary to put in more of the story than I’d first planned. This isn’t an academic post, however I’ve done my best to reference events and individuals, as well as indicate controversies where they exist. As there’re so many dates, I’ve added a timeline at the end to provide an overview, and a reference section for anyone who wants to read further.

During my research I stumbled on some amusing anecdotes, such as the one of the bridegroom persuaded by the young Rajguru and Sukhdev to run away just before his marriage ceremony, purloining the wedding gifts of cash, to be contributed to the cause; only returning to his panicked family and bride-to-be at the insistence of Bhagat Singh. Yet Bhagat Singh himself ran away when his parents wanted to arrange a marriage for him, reputedly leaving a letter saying, “As long as my country is held in slavery, the only bride I will embrace is death.”

I hadn’t known much about the Ghadar Party, its significance, or the U.S. connection, including the meetings held at Stockton Gurdwara (California). A gurdwara my grand-uncle helped to set up, who may well have attended some of those meetings and whose photograph used to hang on the wall there, as I was lucky enough to see when I visited in 2008. However, as Professor Chaman Lal notes, writing in 2013: “The Stockton Gurdwara…. where a hall still stands in the name of Gadari Babas, has been taken over by Khalistan sympathisers…” (‘Gadari Babas’, basically means ‘the honourable Gadari Elders’). Professor Chaman Lal adds that many of the old photographs have been removed. He further writes: “The Gadar movement was one of the most important events in the radicalisation of India’s freedom struggle...”

Like most British-Asians of Indian origin, I’d always been aware of Bhagat Singh as a great hero of the independence movement, but hadn’t known he was also a writer, editor, and voracious reader, who contributed intellectual force and analysis to the freedom movement, and is regarded as a genius by many. Neither had I known he was the one who came up with the immortal slogan “Inquilab Zindabad” (“Long Live Revolution”).

*****

31stJuly dawns. A man awaits the hangman’s noose.

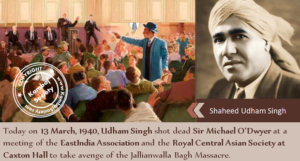

It’s 1940, Pentonville Prison and the man is Udham Singh. Sentenced to death for the killing of Sir Michael O’Dwyer, a former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab in colonial India.

Twenty-one years previously their destinies had collided on 13thApril 1919. Udham Singh, an orphaned young man was in Jallianwala Bhag, a walled garden in Amritsar, helping to serve water to people who had come from the surrounding areas for the religious festival of Baisakhi, and those who had come for a meeting against the repressive measures of the colonial government. The crowd comprising men, women and children, was unarmed and peaceful.

Empires by their very nature exist by the rule of force, brutality and dehumanisation. Their raison d’être is the enrichment and aggrandisement of the mother country. The British empire was no different, despite the rose-tinted veil so often thrown over it.

If, as Shakespeare wrote “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown,” then I say, fearfully lie the heads that run empires. Power is the most jittery of psychological states, existing in constant terror of attack and rebellion. Just look at The Hunger Games. The powerful, ever apprehensive and suspicious, can only survive by instituting regimes of suppression, subjugation and violence. Masterfully illuminated by E.M. Forster in A Passage to India, when Adela, in the depths and darkness of a Malabar cave, imagines Aziz has assaulted her, expressing the colonialists’ prevalent sense of threat from the ‘Brown masses.’

In Amritsar, on 13thApril 1919, in a climate of severe repression, General Dyer (no relation to Sir Michael O’Dwyer) entered Jallianwala Bagh with his troops, sealed off the only exit and ordered his men to fire, and continue firing. Horrifically, they only stopped when their ammunition ran out. Blood drenched the ground. A massacre had been deliberately perpertrated. Adding inhumanity to mass murder, a curfew was declared, preventing aid reaching the wounded, adding to the death toll and blocking families from recovering the bodies of their loved ones. General Dyer later admitted his aim had been to ‘strike terror into the heart of the Punjab…’ He had the full support of Sir Michael O’Dwyer who wrote to him: ”Your action is correct. The Lieutenant Governor approves.”

If truth is the first casualty of war, then truth and justice must be the fist casualties of empire. Two days after the massacre of Jallianwala Bhag, on 15thApril Lieutenant Governor O’Dwyer imposed martial law, with the permission of the Viceroy, and added to the crushing weight of subjugation by backdating it to 30thMarch. Which meant that anyone who had been arrested from 30thMarch could be tried by a military court. Resulting in 264 being transported for life (presumably to the brutal penal colonies in the Andaman Islands) and 108 sentenced to death. Summary courts also ordered flogging as a punishment; a wedding party was flogged for being an illegal gathering.

Dyer’s most notorious decree was the ‘crawling order,’ forcing Indians to crawl on all fours along the street where an English missionary, Miss Sherwood, had been attacked; the decree included the people who lived in the street. Quite irrespective of the fact a Hindu family had actually rescued and looked after Miss Sherwood.

On the evening of 13thApril 1919, the young Udham Singh must have been shell-shocked and racked by what he’d witnessed. But his day wasn’t yet done with Jallianwala Bhag and the bullets of the British. Responding to the grief of a woman called Rattan Devi, he defied the curfew, went to Jallianwala Bhag to recover her husband’s body, and found himself shot and wounded.

Living in Amritsar, Punjab, Udham Singh (or Udham Singh Kamboj to give him his full name) felt the heavy hand of Lieutenant Governor O’Dwyer; the constant tyranny and exploitation. He became active in the independence movement, becoming friends with the freedom fighter Bhagat Singh, whom he regarded as a mentor and an inspiration. In the early 1920s he began his travels, which would take him to East Africa and the U.S.A. where he’d work with the Ghadar Party.

“Bombs and pistols do not make a revolution. The sword of revolution is sharpened on the whetting-stone of ideas.” (Bhagat Singh)

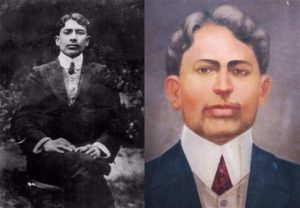

In London, in 1909, Madan Lal Dhingra was tried for the assassination of Sir Curzon Wylie, a former member of the Indian Political Department, and sentenced to death by hanging. “I believe that a nation held down by foreign bayonets is in a perpetual state of war.” Madan Lal Dhingra had said as he went to the gallows in Pentonville Prison. Dhingra had become a hero for the revolutionaries. Even Winston Churchill is reported to have called his statement to the court “[t]he Finest ever made in the name of Patriotism.” In a strange twist of fate, sixty-five years later in 1974, Madan Lal Dhingra’s coffin was accidentally discovered while authorities were searching for the remains of Udham Singh.

Madan Lal Dhingra (Mythical India)

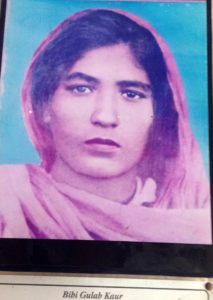

In San Francisco in 1913, the Ghadar Party was founded. The founders were mainly Punjabi and came from Sikh, Hindu and Muslim backgrounds. Ghadar is an Urdu word meaning “revolt” or “rebellion.” The Ghadar Party’s main aim was to liberate India from British colonialism, and establish an independent India for all. (It’s really important to note that Indian freedom fighters came from all backgrounds and didn’t just want to get rid of the British, but had a clear vision of a progressive, secular India with justice and equality for all.) The Ghadar Party organized itself in cells among Indian communities across the world. One of their most active supporters was the wonderfully named Gulab Kaur, (Rose Kaur), who lived in Manila, kept a vigilant eye on party presses in disguise, and often posed as a press reporter to pass arms to Ghadar party members. Later, leaving her husband, she came to India to work for the cause. When captured, she endured two years in a Lahore jail, having been sentenced for ‘seditious acts.’ Sweta Ganjoo writes, she suffered inhumane torture, while imprisoned. Not surprising, as the authorities will have wanted to extract information from her about members of the Ghadar party and its networks.

In 1915 the Ghadar conspiracy, also known as the Ghadar mutiny was attempted by Ghadar party members, but failed as their group had been infiltrated by agents and they were betrayed. This came to be known as the First Lahore Conspiracy Case, as it was heard in Lahore. The Ghadar Party members may have failed in their attempt but Sir Michael O’Dwyer, regarded their ideas as “by far the most serious attempt to subvert the British rule in India,”

details from photo by Kesar Singh taken at Amritsar Railway Station of Sikh political prisoners held in shackles & chains by the British authorities, 1938. Courtesy: Amarjit Singh Chandan Collection. Members of the Ghadar Party, the men are, from left to right:1. Santa Singh Gandivind 2.Dharshan Singh Pheruman. 3. Fauja Singh Bhullar. 4. Sohan Singh Bhakna (first president of the Ghadar Party. 5. Karam Singh Cheema.

In 1914, the Komagata Maru incident occurred. Udham Singh would have been 15 at the time, living in the orphanage, and would probably have heard about it and been aware of the outrage expressed by people. An incident yet again demonstrating to Udham Singh and thousands of others, the ways in which Indians were controlled and violently treated. The injustice, inhumanity and racism of the Komagata Maru Incident has continued to live in people’s minds, and stood as an accusation against the Canadian government. After decades of pressure, finally achieving an official apology from Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau, in 2016.

The Komagata Maru was challenging Canada’s Continuous Passage regulation, requiring travel to be directly between the country of origin and Canada; a racist regulation aimed at keeping out Indians, who couldn’t fulfil it, as the main immigration routes didn’t offer direct passage to Canada. Gurdit Singh, a Punjabi busnessman decided to challenge this regulation by hiring a ship in Hong Kong, to help those whose previous attempts had been blocked, to ease the way for others, and as he said “The visions of men are widened by travel and contacts with citizens of a free country will infuse a spirit of independence and foster yearnings for freedom in the minds of the emasculated subjects of alien rule.”

The passengers comprised 340 Sikhs, 24 Muslims, and 12 Hindus. After an arduous voyage, when the ship arrived in Canada, its passengers packed and ready to disembark, it was refused permission to dock. A prolonged and bitter confrontation ensued with the Canadian government. Food and water was withheld from the ship, the passengers’ communication with those on shore was restricted, an attempt to forcibly board the ship by the police was mounted, a navy ship and troops were mobilised, and racist meetings were held against them. On shore, a group of Punjabis and other South Asians came together to support them: This injustice wounded Bagga Singh and many members of the Indian Canadian community deeply. With eleven other men Singh formed the ‘Shore Committee’, and mounted a court challenge. The Committee’s first meeting drew 500 people from the Indian community . About twenty white supporters and a few reporters were also in attendance. The meeting was called to order and the most urgent order of business quickly addressed. They needed hard cash – enough to keep the ship in Vancouver while its status was negotiated. The hall was full of men who had never banked but carried savings in their pockets or turbans. Money spilled out; a pile of five, ten, and even one hundred dollar-bills rose on a table in front of the speakers. The largest contribution was $2,000.

The ‘Shore Committee,’ hired lawyers, lobbied on behalf of the ship, and on several occasions sent out supplies when conditions became desperate. Unknown to them, In the shadows, some punjabis had become informants and were passing information to W.C. Hopkinson, a British immigration official. Notwithstanding the efforts of the supporters, on July 23rd the ship was forced to turn around and sail back. Later in 1914, two of the Punjabi informants were found murdered and Hopkinson himself was gunned down at the Vancouver Courthouse.

After another onerous sea voyage, when the Komagatu Maru finally docked at Budge Budge harbour in West Bengal, the police boarded the ship, attempting to arrest Gurdit Singh and others. Shots were fired and nineteen men were killed, many wounded and others arrested.

The Komagata Maru Incident was yet another addition to the injustices and violence suffered by Indians, adding urgency and fuel to the revolutionary movements.

By the mid-1920’s Udham Singh was in the States, travelling across the country, working for the revolutionary Ghadar Party, under the guise of aliases, such as Sher Singh, Ude Singh and Frank Brazil. In 1927 Bhagat Singh asked him to return to India with arms and men.

Back in the Punjab, Udham Singh devotes himself to publishing the newspaper Ghadr-Di-Gunj (Voice of Revolt), a prohibited paper, for which he’s eventually arrested and sentenced for five years. It’s while he’s still in prison he learns that Bhagat Singh, along with Rajguru and Sukhdev have been executed by hanging.

“It is necessary for every person who stands for progress to criticise every tenet of old beliefs,” Bhagat Singh had written in an article; as well as writing the essay Why I Am An Athiest. Only 23 at the time of his execution he had become a charismatic figure. Passionate and willing to sacrifice everything, he had endured a hunger strike for 116 days, the longest at that time; only ending it when his father, himself a revolutionary and Ghadarite, begged him to do so, as well as the Congress Party.

In 1928 Bhagat Singh and Rajguru (with the complicity of others) had shot Assistant Superintendent of Police John Saunders. They’d intended to shoot Superintendent James Scott, whom they blamed for the death of Lala Lajpat Rai, who had been severely beaten on a demonstration.

In what came to be known as the Second Lahore Conspiracy Case, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced for the murder of John Saunders. Bhagat Singh was also sentenced for the bombing of the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi, in 1929 with Batukeshwar Dutt (who was given a prison sentence and sent to the horrific cellular jail in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands).

“If the deaf are to hear, the sound must be very loud.” Bhagat Singh had said. The bombing

(as dramatised in this clip from the 15 minute film The Legend of Bhagat Singh) wasn’t designed to cause fatalities but to draw attention to their protest against ever more repressive laws being passed. After throwing the small bombs, the two sent down a rain of leaflets, explaining their action and then allowed themselves to be arrested. Bhagat Singh wanting to use the courtroom as a platform for spreading the ideas of the revolution; to argue against the raj, in the heart of the raj.

In prison, Bhagat Singh was horrifically tortured, tied naked to blocks of ice and severely lashed all over his body.

Sentenced to death with Rajguru and Sukhdev, their execution was brought forward by 11 hours, to 23rd March 1931 at 7.30pm, (I’ve read that executions were normally carried out at 8am in the morning), denying family members a last meeting, and their bodies immediately disposed of, so no proper funerals could take place. It’s said that shouts of ‘Inquilab Zindabad,’ were heard from within the walls of the jail.

Many unanswered questions had been raised by the manner of the execution and its aftermath. It was generally believed the English had tried to circumvent public grief and anger. However a book published in 2005 puts forward an altogether more ghastly and vengeful explanation. Titled, Some Hidden Facts: Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh, it carries the subtitle “Secrets unfurled by an Intelligence Bureau Agent of British-India,” the book describes a conspiracy called ‘Operation Trojan-Horse,’ which ‘facilitated the pacification of the British officers in general and the prospective in-laws of the late J P Saunders in particular. Accordingly, Bhagat Singh and his associates did go through the formality of ‘hanging’ but only to the extent of breaking their necks; semi-conscious, they were taken to the Lahore Cantonment where the ‘Death Squad’, comprising Saunder’s family, shot them to quench their thirst for revenge.’ The book goes on to say, the bullet-ridden bodies were secretly burnt to ashes and a decoy pyre was organised; the families deceived into believing it was the burning remains of their young men.

Women’s contribution to the independence struggle is often overlooked, although they also  marched, sacrificed and lived a life of danger. Durga Devi Vohra, alias ‘Durga Bhabhi,’ was one such woman. This unsung revolutionary appeared like a meteor on the anti-colonial nationalist sky and wielded tremendous influence on men such as Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Chandrashekhar Azad

marched, sacrificed and lived a life of danger. Durga Devi Vohra, alias ‘Durga Bhabhi,’ was one such woman. This unsung revolutionary appeared like a meteor on the anti-colonial nationalist sky and wielded tremendous influence on men such as Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Chandrashekhar Azad

In December 1928, after having killed John Saunders, Bhagat Singh and Rajguru were being hunted by British Intelligence and hundreds of police officers. In an effort to protect themselves they had changed their appearance, cutting their hair and wearing western clothes. With Durga Bhabha’s help, a daring escape plan was devised.

With Bhagat Singh posing as an Anglo-Indian, carrying Durga Bhabhi’s three-year old son, Durga pretending to be his wife, and Rajguru their servant, the ‘family’ made their way through the massive police cordon to the train station, where they boarded a first class train carriage for Lucknow.

Around the same time, Chandrashekar Azad was helped to escape Lahore by Sukhdev’s mother and sister. Chandrashekar disguised as a sadhu ‘escorting’ the two women on a pilgrimage.

Such acts may sound simple but required nerves of steel and the willingness to risk life and liberty.

Amidst tumultuous times, after the bombing and leafletting of Delhi’s Central Assembly, Durga’s husband had to flee and go into hiding, his bomb factory having been discovered. Durga took on the risky role of ‘undercover post-box’ for revolutionaries and their families and attempted an assassination of Lord Hailey, a hated ex-governor of Punjab. Whilst in hiding, her husband was trying to perfect a device to bomb the jail where Bhagat Singh was incarcerated and free him. Unfortunately, on the banks of the river Ravi, a test device exploded and killed him on the spot.

Heartbroken, Durga stepped up her revolutionary activities, leading demonstrations and in October 1929, shooting a British policeman and his wife in Bombay (Mumbai), resulting in her capture and imprisonment. An incident later to be described as “the first instance in which a woman figured prominently in a terrorist outrage”.

In the film Rang De Basanti, the character played by Soha Ali Khan is based on Durga Devi.

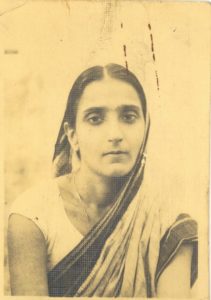

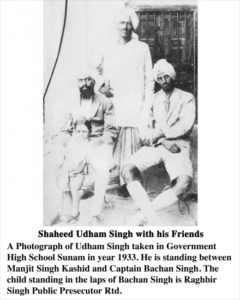

This photograph of Udham Singh was taken after he had been released from prison, and shows a thin and suffering man. Working as a signboard painter, at some point Udham Singh has his most famous name tattooed on his arm: Ram Mohammed Singh Azad. Combining Hindu, Muslim, Sikh names and adding Azad, the word for freedom. The police continued to monitor and harass him after his release. Eventually forcing him to leave India.

In England in the late 1930s, Udham Singh, helps to set up the original Indian Workers’ Association (GB), which aims to raise support for the independence movement and Indian workers in England, and was to be an important organisation for Indian workers with branches in major cities such as Birmingham and Coventry, tackling racism and unfair work practices.

After 13thMarch 1940 as Udham Singh awaits trial in Brixton Prison, having clearly stated his motives for assassinating Sir Michael O’Dwyer, the authorities are anxious to hide the political nature of his action and to try his case as one of ‘simple and mindless murder.’ ‘In the words of the C.C. (CID): “In this clear-cut murder case in which the ordinary evidence is very strong, it will be a pity if all the ‘rubbish’ which came from the lips of the prisoner is to come out in Court, and then in the newspapers.”

In a court document dated 5.6.40. Udham Singh has written what must be part of his speech to the court. I have no idea if he was able to deliver it, but here are some of the points he makes:

“British terrorism in India….India has been made a slaughterhouse… . Many women had their hair violently pulled and brought into the street where they were insulted and sharp instruments inserted into their bodies. Many died under the blow of the English blood bath, many had their faces mutilated, even their eyes taken out.”

Sheet “C” contains material copied from Udham Singh’s diary. It notes, “In the top right hand corner appears the following in Gurmukhi:” “1932 near Peshawar villages were burnt, clothes were removed, women and children were stripped naked. This went on for about three weeks ….”

It’s easy to mythologise people like Udham Singh who sacrificed their lives for the cause of freedom, and to forget they had other aspects to their characters. I was captivated when I came across a YouTube video in which his love of the epic poem Heer , a Punjabi classic by the sufi poet Waris Shah about the star-crossed lovers Heer and Ranjha, is revealed (from 6.00 – 8.00). As well as his desire to take his oath upon it at the Old Bailey. Apart from being a powerful and tragic love story, Heer is also a cry against tyranny. Udham Singh appears to regard it as a sacred text, in the sense that it carries truth. As a writer, I believe literature is a way of progressing towards the truth or gaining glimpses of it. He writes that he’s been refused permission to take his own copy of Heer into court and requests that a copy be acquired for the trial. It’s not known if a copy was made available and if he was allowed to take his oath on Waris Shah’s wonderful Heer. (The same Waris Shah to whom Amrita Pritam addresses her harrowing poem about the Partition: Aj Aakhan Waris Shah Nu ).

In 1974, Sadhu Singh Thind, a member of the Legislative Assembly of India, persuaded Indra Ghandi to force the British to hand over Udham Singh’s remains, which he then accompanied back to India, where the remains were given a martyr’s reception.

Statues and monuments may have been erected to the freedom fighters, who not only fought for independence from British oppression, but for a secular India of universal equality. A vision cruelly disappointed by the rise of right-wing Hindu rule, violence against Muslims, Sikhs, and other minorities. A true monument to the freedom fighters would be a secular nation with an ethos based on equal opportunities and proper democratic governance. Such changes take decades upon decades, requiring thoughtfulness, scrutiny and adjustments, but it would be the strongest path India could take and the one for which the freedom fighters and Udham Singh sacrificed their lives.

The film Rang De Basanti, (Colour Me Saffron) successfully makes this very point, about the unity of the freedom fighters who came from different backgrounds and their vision of a progressive India where all had rights. Successfully flitting between contemporary India and the past, the film draws parallels between prevailing corruption, the oppression of the past, and the courage and legacy of the freedom fighters.

A legacy heartbreakingly crushed even as Independence was finally achieved. The Partition tearing apart communities that had always lived together, unleashing terrible hatred and violence. Movingly captured in this trailer from the documentary ‘Rabba Hun Kee Kariya (God What Shall We Do Now) Thus Departed Our Neighbours, by Ajay Bhardwaj.

In our own time, as we hear of refugee ships searching for a place to dock, the Komagata Maru reminds us todays tragedies aren’t alien to us, and we owe them our help and support. The globe is big enough and abundant enough to support us all, if we didn’t distort international and national relationships with fear and aggression, just as the power wielders of the British Raj did. The planet’s increasing inter-connectivity should be used for establishing co-operative discourse and evolving new business models. Nothing is beyond our capacity. If a country which was ruled for two hundred years by an iron fisted power could liberate itself, then….

I’m going to finish in true Bollywood style with the title track from the film ‘Rang De Basanti‘ released in 2006.

Some background information: The song Rang De Basanti is popularly associated with Bhagat Singh. Several films depict Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev singing it as they go to the gallows, although this may be a transposition of what really happened, as it was reported freedom slogans were heard being shouted within the jail, on the evening of their hanging. The song is attributed to Ramprasad Bismil and his associates, who were in jail in the spring of 1927, (Basant – is the season of spring – and associated with the vibrant colour of yellow or saffron). This song went on to become one of the most iconic songs of the pre-independence era, and post-independence also.

In this video from the film, ‘Bismil’ refers to Ramprasad Bismil who led a team of 10 revolutionaries in an audacious raid on a train at the town of Kakori, in 1925, transporting money they firmly believed belonged to India, but was destined for the British Treasury. https://bit.ly/2vs6ihG

Rang De Basanti, is a complex tale about political awakening and sacrifice using the device of a film-within-a-film. A young Englishwoman arrives to make a documentary, based on her grandfather’s diaries, James McKinley, one of the wardens administering the imprisonment, torture and execution of the young revolutionaries.

*****

See also : Udham Singh, The Lonely Revolutionary

My thanks to Tajender Sagoo at Frankbrazil.org, Ajay Bhardwaj for permission to use the trailer for ‘Rabba Hun Ki Kariye, Thus Departed Our Neighbours.’ And Rukhsana Ahmad.

*****

Further Notes:

UDHAM SINGH

1. There appear to be questions about whether Udham Singh was actually present at Jallianwala Bhag on the day of the massacre. The Tribune newspaper quotes Dr. Navtej Singh, who says, according to his research, Udham Singh was abroad on that terrible day, “but returned to the holy city (Amritsar) a few months after the momentous incident, which undoubtedly influenced him deeply and determined the course of his life,”. Dr. Singh places him as working for North Western Railways from 1917 to 1922. Further in the article Professor M.J. S. Waraich quotes Udham Singh as having been in Africa at the time of the massacre.

2. The Open University in its ‘Making Britain’ series, records that the Amritsar massacre, had left a lasting impression on Udham Singh as his brother and sister were killed there. It also places him in Dover, for three months in 1921, and then in the United States, working in Detroit and California, returning to India in 1927 – at which point all roads converge, as in 1927 in India, he was arrested and imprisoned.

3. Suffice it to say, possibly because of Udham Singh’s extensive travels and name changes, more sifting and analysing needs to be done. The truth remains that he dedicated his life to the Indian independence struggle. There can be no doubt about his pain and anger at the violence, degradation and inhumanity suffered by Indians, the systematic impoverishment of the country, his horror at the Jallianwala Bhag massacre and his desire to strike back, and strike a blow for freedom.

Udham Singh’s trial and restriction on information: https://bit.ly/2n4BU9b

Heer by Waris Shah: https://bit.ly/2LM1jTP

Indian Workers Association: https://bit.ly/2vN26cj

JALLIANWALA BHAG

As 2019 will be the centenary of Jallianwala Bhag I’m sure there’ll be a clutch of books coming out. Personally, I’m looking forward to Anita Anand’s book on Udham Singh “The Patient Assassin: A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj“. As well as Kim A. Wagner’s “Amritsar 1919. An Empire of Fear & The Making of a Massacre” to be published by Yale University Press, February 2019.

The Amritsar Massacre: History Ireland https://bit.ly/2LPeDH2

Baisakhi: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaisakhi

THE PENAL COLONIES on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

The Cellular Jail: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cellular_Jail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ross_Island_Penal_Colony

Inside Cellular Jail: the horrors and torture inflicted by the Raj on India’s political activists

The Guardian.com: Survivors Of Our Hell

GULAB KAUR

For those who want to do more reading on her, Gadar Di Dhee Gulaab Kaur (Daughter of Ghadar Gulab Kaur), written in Punjabi by S Kesar Singh is available. (Plea: perhaps some scholar could translate this book into English?) Revolvy has some information on her too: https://www.revolvy.com/page/Gulab-Kaur

GHADAR PARTY

An informative and very good history of the Ghadar Movement by Jaspal Singh.

Ghadar Memorial in San Francisco: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Ghadar-Memorial/213950855392294

http://legacy.sikhpioneers.org/gadarphoto.html

Role of Oregon Sikhs in the Ghadar Party: https://bit.ly/2MjZfi9

Seema Chisti, Indian Express Archive: “From U.S. The effort to free India from British: https://bit.ly/2LVkf2I

Professor Chaman Lal blog post: “On Ghadar Party Centenary in EPW”: https://bit.ly/2OfLlOK. His blog notes that Bancroft Library of University of California, Berekely holds: “… a Gadar archive with 20 boxes of documents and some digitised records.” Professor Chaman Lal further notes: “The Gadar Movement was the most advanced secular democratic movement of its time whose tradition was upheld and appropriated by Bhagat Singh later with further addition of the socialist ideology.”

BHAGAT SINGH and HIS COMRADES

Essay: Why I am an Athiest: https://bit.ly/2Hwv4Ba

Bhagat Singh Quotes: https://bit.ly/2MnjtYn

Lahore Tribune’s Front Page, announcing execution: https://bit.ly/2ODTH3C

The 15 min short film: encapsulating Bhagat Singh’s life. https://youtu.be/-E2WWskbbqk

This article ends with the story of the famous photograph in the hat: https://bit.ly/2OcSpLX

Text of Leaflet thrown in Central Assembly Hall: https://bit.ly/2OKYEYI

Article on Bhagat Singh including a description of the jail cell known as Phansi Ki Kothi (Cottage of Hanging) https://bit.ly/2Kt9oHG

Operation Trojan Horse: The Sunday Tribune – Spectrum: Book Review: Hidden Facts: Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh. Subtitled: Secrets Unfurled by an Intelligence Bureau Agent of British-India. https://bit.ly/2MdmHOe

Shivaram Rajguru: https://bit.ly/2LLeu7y

Sukhdev Thapar: https://bit.ly/2vfBd1i

Durga Devi: https://bit.ly/2OKSozT

University of Iowa: analysis of the film: Rang De Basanti: (The Colour of Sacrifice): https://uiowa.edu/indiancinema/rang-de-basanti

MADAN LAL DHINGRA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madan_Lal_Dhingra

http://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/madan-lal-dhingra

https://darkestlondon.com/tag/madan-lal-dhingra/

http://mythicalindia.com/features-page/madan-lal-dhingra-biography-family/

KOMAGATA MARU INCIDENT

Simon Fraser University Library http://komagatamarujourney.ca/intro

Justin Trudeau’s live apology for the Komagata Maru Incident: https://bit.ly/2O4XINq

Komagata Maru: Continuous Journey Regulation: chttps://bit.ly/2AwZ2a5

Gurdit Singh, who chartered the Komagata Maru: https://bit.ly/2n6pTjP

Canadian Museum for Human Rights: https://humanrights.ca/blog/story-komagata-maru

Passage from India: https://bit.ly/2BIZe6H

Description of documentary film by Canadian based director Ali Kazmi, Continuous Journey from Third i NY: https://bit.ly/2vGxbyy

A PASSAGE TO INDIA

By E.M Forster. http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/passage/summary/

AMRITA PRITAM

Articles on Amrita Pritam: https://bit.ly/2zQCcru https://bit.ly/2OFsSPG

A feminist perspective: https://bit.ly/2RpzdNy

Ten quotes from Amrita Pritam on everything that matters: https://bit.ly/2RpzdNy

Obituary: The Independent UK. https://ind.pn/2zRzYZ7

Gulzar, poet and film director, recites Aj Aakhan Waris Shah Nu, with an English translation.

TIMELINE

- 1849 Punjab annexed to British Dominions

- 1899 Udham Singh born in Sunam, Punjab, 26th December

- 1907 Bhagat Singh born in Banga, near Lahore, 27th September

- 1909 Madan Lal Dhingra shoots Sir Curzon-Wyllie. Hanged at Pentonville

- 1913 Ghadar Party founded in U.S.A

- 1914 Komagata Maru Incident

- 1915 Ghadar party conspiracy, also known as the Ghadar Mutiny

- 1919 Jallianwala Bhag massacre

- 1925 ‘Bismil’ leads raid on train at Kakori

- 1927 Udham Singh arrested and sentenced to 5 years in prison

- 1928 Bhagat Singh and Rajguru shoot Saunders and go on the run

- 1929 Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt bomb and leaflet the Central Legislative Assembly.

- 1931 Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev are hanged

- 1933 Udham Singh released from prison. Goes abroad. In the 1930’s helps found IWA (GB)

- 13-3-1940 Udham Singh assassinates Sir Michael O’Dwyer

- 31-7-1940 Udham Singh hanged at Pentonville Prison

- 1947 Indian Independence Act (July 1947) sets out Partition

- 1947 Night of 14/15th August, India and Pakistan become independent states

- 1947 August: Partition holocaust rages

- 1974 Udham Singh’s remains repatriated to India

Bhagat Singh is real hero of every real Indian. your article is informative and realstic about great freedom fighter