‘Ambarsar.’ That’s how I used to hear it as a child. The pronunciation soft and flowing, echoing its meaning of lilting water: a place that was both temporal and divine, both real and rather magical. The name means “Pool of the nectar, of immortality.”

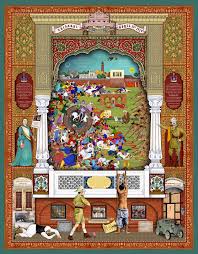

For most Punjabis, particularly Sikhs, Ambarsar, or Amritsar as it’s more commonly known, occupies its own place in the hinterland of their consciousness; possessing as it does, the sacred Golden Temple and the blood-drenched Jallianwala Bagh.

However, with the centenary of Jallianwala Bagh occurring on 13thApril 2019, Amritsar came to the forefront of our attention, with the Channel 4 documentary The Massacre That Shook the Empire, and the publication of a slew of books.

Coming from a Punjabi family I’d unconsciously absorbed the story of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, without knowing many of the details. My real engagement with Amritsar’s history and the massacre, began with the discovery that Udham Singh had been held at Brixton Prison, after he assassinated Sir Michael O’Dwyer, former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab (no relation to General Dyer). Living in South London, over the years, I’ve driven past Brixton Prison hundreds of times, often glancing towards its ominous structure, wondering about the inmates. Discovering Udham Singh had been imprisoned there while awaiting trial, aroused my curiosity. He’s now included on their list of ‘Notable Prisoners’, along with Bertrand Russell, Mick Jagger and others. I’ve been surprised to see my blogs on Udham Singh and the Indian freedom struggle, being accessed on a daily basis. It’s clear there’s a growing and committed interest in what I call British-Asian history, as evidenced by the work of such disparate people as Rozina Visram and art collector Davinder Toor.

Like thousands of others, I watched the documentary The Massacre That Shook the Empire. Of the books, the ones I’ve managed to read are Eyewitness at Amritsar, The Patient Assassin and Amritsar 1919. I almost feel as if I’ve flitted ghost-like through the streets of the Amritsar of a hundred years ago; an Amritsar in the grip of draconian laws, imperial panic and savage violence. I’m going to focus on the documentary because of the issue of massacre-deniers.

The past isn’t a neutral place. It still hurts and holds us. Truth and justice still need to be applied to it. Not many of us will have known the full details of what happened at Jallianwala Bagh on 13thApril 1919, but we may have known the gist of it: that thousands of peaceful, unarmed people were shot, killed and wounded in an enclosed park, by Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, who’s often referred to as ‘the Butcher of Amritsar.’

The Massacre That Shook the Empire broadcast on the centenary of the massacre, preceded by interviews and discussions, promised to be powerful and poignant; speaking truth to the empire and presenting truth to those whose knowledge of the massacre was sketchy at best or only derived from British historians. After it was screened much praise was heaped upon it, but there were also many dissenting voices, mine included.

The documentary was presented in the mode of ‘personal discovery.’ Sathnam Sanghera, a forty-something, British-Asian of Punjabi heritage, sets out to discover the history of Jallianwala Bagh. And who are the first people he chooses to speak to? Reginald Dyer’s great-granddaughter and the grand- children of Ronald Beckett, Assistant Commissioner in Amritsar at the time of the massacre. All of them massacre-deniers.

The documentary was presented in the mode of ‘personal discovery.’ Sathnam Sanghera, a forty-something, British-Asian of Punjabi heritage, sets out to discover the history of Jallianwala Bagh. And who are the first people he chooses to speak to? Reginald Dyer’s great-granddaughter and the grand- children of Ronald Beckett, Assistant Commissioner in Amritsar at the time of the massacre. All of them massacre-deniers.

I ask the question: if someone was making a documentary on the Holocaust, would they first go to Holocaust-deniers?

Sathnam justifies his interviews with the descendants, by quoting a family story where one relative has killed another. The analogy doesn’t equate, one killing does not a massacre make. Secondly the relationship of empire to subject is one of unequal power, dehumanisation, and ruthless exploitation of the country’s people and resources. Empires are created through violence and sustained by violence; savagery is deployed to intimidate, terrify and control. Read the accounts of the brutality endured by political prisoners in the British cellular jails on the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Empires exist purely to increase the wealth, power and prestige of the mother country. During his trial Udham Singh declared “India is only slavery. Killing, mutilating and destroying – British Imperialism. People do not read about it in the papers. We know what is going on in India.”

Accountability and morality are important because they’re values in themselves; as well as contributing to justice and setting precedents. Massacre-deniers evade both. I understand the impulse to shy away from the actions of ancestors, who’ve committed acts so horrendous they touch the gauge of crimes against humanity. But ‘shying away’ is very different to making counter-accusations and victim blaming.

Accepting truth is perhaps our greatest challenge and the one we’re least successful at meeting. It appears to me truth and justice are two sides of the same coin. If we accepted truth, we’d have to accept justice. And if we accepted justice, the world would be a very different place. Perhaps our governments would deal with climate change as the emergency it is; perhaps we’d have fewer wars and less poverty. When it comes to atrocities the truth casts a dark generational shadow. I’ve gained a small insight into the pain and anguish such a connection can cause to descendants.

Recently, whilst researching my grandfather’s military service in the First World War and his regiment, the 25th Punjabis, I came across the name of the Commanding Officer. A certain Reginald Dyer. I was at the British Library, and though the period I was reading about was 1914 and the regiment was stationed in Hong Kong at that time, my heart went absolutely cold. I had to shut the book and leave the reading room.

Recently, whilst researching my grandfather’s military service in the First World War and his regiment, the 25th Punjabis, I came across the name of the Commanding Officer. A certain Reginald Dyer. I was at the British Library, and though the period I was reading about was 1914 and the regiment was stationed in Hong Kong at that time, my heart went absolutely cold. I had to shut the book and leave the reading room.

The British Library has open spaces, working areas and cafes. I remember sinking onto the first bench I came across and sitting there in a daze of icy fear. My mind had jumped five years ahead to 1919, to Amritsar, to Jallianwala Bagh. Such is the resonance of Dyer’s name. Questions bubbled like sulphur in my head. Had Reginald Dyer continued to command the 25thPunjabis till April 1919? I’d been told my grandfather had left the army after the war, but no-one in the family knew if it was in 1918 or 1919. If my dread turned out to be true, how on earth were we, the whole family going to live with such knowledge? With a blood-stained inheritance? We’d be forever changed, forever charged with a terrible responsibility. Would we have the courage to shoulder it? How would we pass it on to our descendants?

I went back into the reading room, changed my books, concentrated on tracing Reginald Dyer’s service history, and went limp with relief, my heart unclenching, breath easing. Dyer is recorded as leaving the 25th Punjabis and arriving in Rawalpindi on 13th December 1914, where it appears he was seconded to the 2nd Division. During the war he commanded the Seistan Force.

The records available show he never again commanded the 25thPunjabis. When he left the regiment he’d served almost five years with them, so it’s possible my grandfather, recipient of one of the Durbar and other medals, and a Havildar (equivalent of a sergeant), may have had dealings with him. That’s connection enough.

We humans have a great need to justify our actions, even the most brutal and barbaric. The enslavement of Africans was justified for hundreds of years by categorising black people at the level of animals. Britain’s rule over India was justified in terms of ‘civilising’ the ‘heathen’, and ‘child-like people,’ promoting the paternalistic idea of ‘Ma-Baap’, the benign parents. As Kipling wrote, ‘The White Man’s Burden,’ was indeed onerous, but they did their duty out of the goodness of their hearts. Cue smiling emoji.

Take up the White Man’s burden–

Send forth the best ye breed–

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild–

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

In the documentary, given that the interviews with the massacre-deniers were at the beginning of the programme, and weren’t adequately challenged, we’re left with the impression the ‘Indians were to blame’.

Jallianwala: Repression and Retribution

If the documentary chose to spend a generous amount of time on massacre-deniers, then it had an obligation to give sufficient time to the unremitting horror of the massacre and the savage reign of terror which followed. I found not enough time was spent on the massacre, and no mention was made of the curfew which prevented medical aid getting to the wounded, many of whom died during the long, lonely night. Imagine your life ebbing away, as you lie dying on a killing field, hearing the last cries and groans of others, including children; bereft of all human comfort. There was no water, no help, no rescue.

Not only did the documentary begin with massacre-deniers but the presenter, Sathnam, decided to end it with a massacre-denier too. Caroline Dyer is invited to a discussion with Dr Kohli, whose great-uncle had been caught in the massacre but survived by hiding under a pile of bodies. In what is clearly an arid, stilted encounter, Caroline pounces on an opportunity to call Dr Kohli’s ancestor a looter. And there you have the Raj! So much for truth and reconciliation.

Wondering if I’d been too critical and expected too much from this documentary, I checked out other peoples’ views. A Muslim friend (also of Punjabi heritage) hadn’t been terrifically impressed, and made the point that many Muslims were massacred in the Bagh too, and Muslims feel the atrocity as deeply as anyone else. She described how a cousin of hers had visited Jallianwala Bagh a few years ago and found himself overcome with sorrow, eyes filling with tears. In his book Amritsar 1919, Kim Wagner makes the point the authorities were afraid of Hindu/Muslim unity.

I also spoke to a couple of young British-Asian women, thirty-somethings, Punjabi heritage, British born and bred. One of them said the documentary was rambling and hadn’t held her attention. The other one commented, how it seemed to her Sathnam wanted to appease White people.

Three important issues converge here. The first is that we British-Asians and the audience in general, deserved a stronger piece of work given the historic value of the subject and the significance of a centenary.

Secondly, asking if the empire was racist, really is like asking if the Pope is catholic. The nature of empire needed to be covered (and there was time for it), so the descendants of both Indians and the English can move forward on an equal basis. Knowing the nature of empire, i.e. as untrammelled power, enables us to recognise modern-day incarnations of empire in the form of multi-national companies, tech giants and the Brexit Party – to bring it right home.

Thirdly, why do we need to spend time on, or try to convert massacre-deniers? Why is it our job? There’re are parallels with racism: Afua Hirsch recently articulated the double-bind placed on people of colour after participating in a discussion, on the racist photograph posted by Danny Baker after the birth of Harry and Meghan’s baby, “…not just having to deal with the content of an idea that compares people like me to another species, but of then being expected to persuade people why that’s bad.”

So, massacre-deniers not only expect us to be the ones to prove to them, that a massacre did indeed occur at Jallianwala Bagh, but also that it was the British who were to blame. Just as we want an apology for the massacre, so we should expect descendants to ‘own’ the atrocity. I’m certainly not suggesting they should be blamed or shamed. I believe in discourse, but all sides need to come in good faith and be willing to listen and consider. No-one can say there isn’t enough material on the subject if they want to learn about it. I’ll happily recommend the three books I’ve been engrossed in:

Amritsar 1919. An Empire of Fear & The Making Of A Massacre by Kim A. Wagner.Highly detailed, providing an almost day to day account of how events built up and laying bare the paranoia, contempt and hostility of the English for the Indians.

Eyewitness at Amritsar. A Visual History of the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre by Amandeep Singh Madra and Parmjit Singh. A beautifully produced book, full of old photographs, illustrations, and harrowing eyewitness accounts, taking us into the heart of the massacre.

Eyewitness at Amritsar. A Visual History of the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh Massacre by Amandeep Singh Madra and Parmjit Singh. A beautifully produced book, full of old photographs, illustrations, and harrowing eyewitness accounts, taking us into the heart of the massacre.

The Patient Assassin. A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj by Anita Anand. Telling the story of Udham Singh who vowed vengeance for the massacre. Anita Anand is a natural storyteller and this book is a vivid, absorbing read as it follows the complex Udham Singh, whose turbulent life came to be governed by his vow.

The Patient Assassin. A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj by Anita Anand. Telling the story of Udham Singh who vowed vengeance for the massacre. Anita Anand is a natural storyteller and this book is a vivid, absorbing read as it follows the complex Udham Singh, whose turbulent life came to be governed by his vow.

Leave a Reply